Introduction to the RSP Notebook Aspect¶

Most RSP users will find Jupyter Notebooks to be the most efficient and powerful way to interact with the LSST data sets.

Always save and shutdown all notebooks and log out of JupyterLab when you are done with your day’s work. This is important to preserve resources for other users and to ensure you re-enter the RSP in a known state every time. To help users avoid issues with stale instances, sessions will be automatically shut-down after 5 days of inactivity, or after 25 days.

This page focuses on the basic instructions for using the RSP Notebook Aspect, and a few FAQs and Troubleshooting Tips. The full documentation for the RSP Notebook Aspect is available at nb.lsst.io.

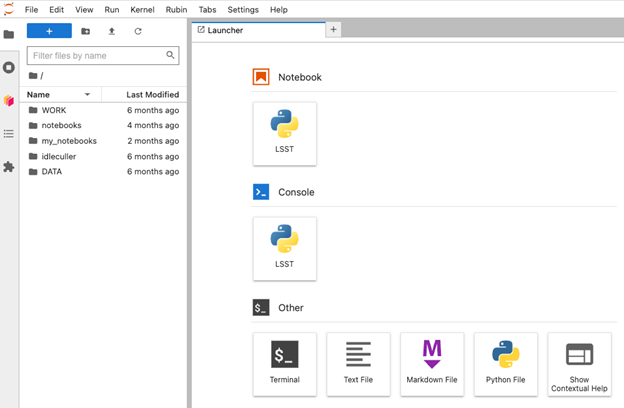

How to use the JupyterLab terminal¶

The DP0.2 Data Products Definition Document (DPDD) and the LSST Science Pipelines tools can both be accessed from the command line of a JupyterLab terminal tab. A terminal session can be started by clicking on the terminal icon in the Jupyterlab launch pad. As described in the default message that appears in all newly-launched terminals, to create a Rubin Observatory environment in a JupyterLab terminal session and set up the full set of packages, users must first execute:

source ${LOADSTACK}

setup lsst_distrib

For example, to query and retrieve data sets using the Butler (see What is the Butler?, below), command-line tools are available as documented here.

Type butler --help in any terminal to see a list of available butler functionality.

How to use a Jupyter notebook¶

Executing code in a Notebook: Jupyter notebooks provide “cells” within which you type either Python code or markdown language (for formatted text). Choose the cell to execute by clicking in it with your mouse (the cursor must be in the desired cell). Hold down the shift key and press either enter or return (depending on your keyboard type), or click the ‘Play’ button in the notebook toolbar, and the contents of the cell will be executed. If the cell type is code, and the cell contains python code, the code will be executed. If the cell type is markdown, then it will be rendered upon execution to yield nicely formatted text. For some handy markdown tips, see this blog post.

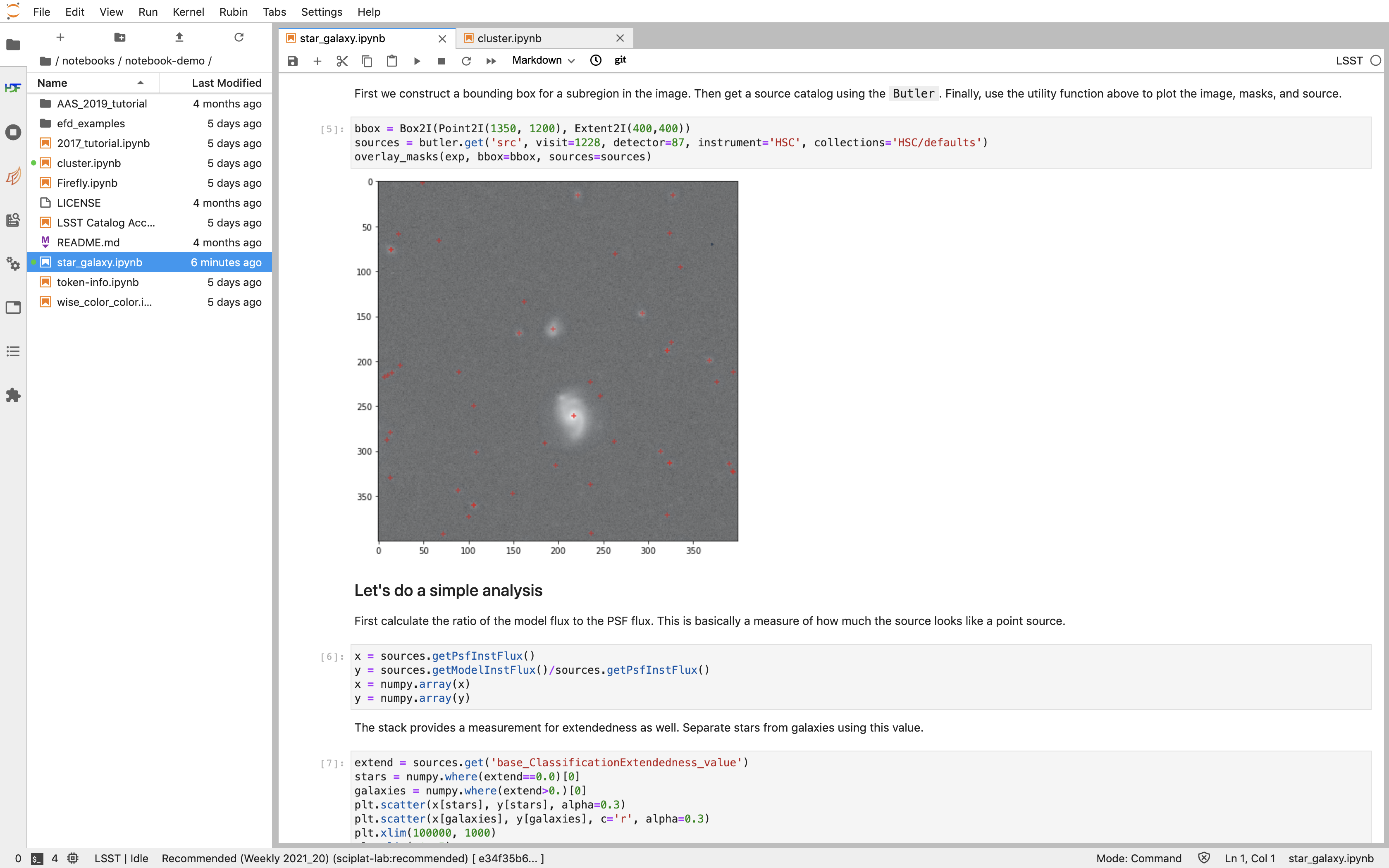

A screenshot from the end of tutorial notebook 01 “Introduction to DP0.2”, showing the panel of the Notebook Aspect where multiple interface tabs can be open at once. In this case, the first tab is a command-line terminal, the second is the Launcher interface, and the third (which is currently selected) is an executed version of tutorial notebook 01. Multiple notebooks can be opened in separate tabs.¶

Opening Multiple Notebooks: You can have multiple notebooks and terminals open in your viewer at a time. This is very handy, but you can also arrange both notebooks and terminals next to or on top of each other by dragging the notebook or terminal around by the top bar. Arranging the windows can be convenient when working in both a terminal and notebook at the same time, or when using another notebook as a reference.

JupyterLab Autosaves Notebooks: Note that JupyterLab autosaves your notebooks at a default interval of 2 minutes unless you are working in the directory “notebooks/tutorial-notebooks/”, which is read-only (see next section).

How to use the Tutorial Notebooks¶

The best way to learn how to use a Jupyter Notebook is to open the first of the tutorial notebooks which are provided in each user’s home directory, and also available in the tutorial-notebooks repository in the “rubin-dp0” GitHub Organization (see also Notebook tutorials).

The “notebooks/tutorial-notebooks” directory is read-only: The read-only “notebooks/tutorial-notebooks” directory will always contain the most up-to-date versions of the tutorials. Notebooks can be edited and executed in this directory, but changes cannot be saved to this directory. Users wishing to edit, execute, and save versions of these notebooks should copy them to a different path in their home directory.

Jupyter notebook frequently asked questions¶

What is a kernel?¶

In the RSP Notebook Aspect, your notebooks will be operating in a kernel that has access to the full LSST Science Pipelines, including the Butler (see What is the Butler?, below). Many standard Python libraries and modules will be available, and users can install additional Python tools they wish to use. See also this tutorial on installing python packages (which includes, e.g., use of “pip install”). To view a list of packages available to you, type “pip list” in a terminal.

Is all the code in Python?¶

Yes, the RSP Notebook Aspect will only have python environments for DP0.

To access data from the Notebook Aspect, users will need to use Python commands and code. Much of the LSST Science Pipelines code is in Python, and the DP0 Notebook tutorials use Python as well. These tutorials contain executable examples of the commands required to access and analyze data. All DP0 delegates should feel free to copy and paste from the provided tutorials.

Anyone new to Python and looking to learn more might benefit from this Python for Beginners website (which includes links to tutorial in a variety of languages), or this Community Forum thread where DP0 delegates can share resources for python beginners. Web searches for “python (thing you want to do)” are usually pretty successful too.

How do I install packages in my user environment?¶

Basic User Installs¶

The Rubin Science Platform (RSP) comes with the rubin-env conda environment, including the LSST Science Pipelines, pre-installed and activated within the Notebook and Terminal.

If you need to extend the rubin-env environment by installing other Python packages to enable your work, you can use the pip install command.

In the RSP, pip actually invokes conda to do its work, ensuring that dependencies that are already present in rubin-env are used (if compatible).

Packages installed with pip will be placed in a subdirectory of your home directory.

These packages are only guaranteed to work when the conda environment in which you installed them is activated.

If you need to install other conda packages but don’t need to use them at the same time as the rubin-env and LSST Science Pipelines packages, you can install them into a new conda environment.

Start by doing source /opt/lsst/software/stack/loadLSST.bash to initialize conda.

Use the conda create -n myenv command to create the new environment.

Use the conda activate myenv command to activate this environment.

Use the mamba install {package} ... command to install one or more packages into the environment.

(mamba is a faster version of conda for installing packages.)

If the package to be installed is not available from the current channels, then the channel will have to be specified, e.g., mamba install -c {channel} {package}.

When you’re done using the environment and want to revert to the rubin-env one, use conda deactivate.

If you need to directly extend the rubin-env environment with other conda packages, the only way to do so at present is to clone the environment.

This is a time- and space-consuming process, so we do not recommend it.

More Complex User Installs¶

Suppose one wishes to install a user package on the RSP that has dependencies on non-python libraries.

Typically, these non-python libraries must be installed and built separately, and the LD_LIBRARY_PATH must be updated.

Leanne Guy created a simple and effective tutorial notebook for working with user packages, using the install of the bagpipes Bayesian Analysis of Galaxies package as an example.

(The bagpipes package depends on PyMultiNest, a python interface to the MultiNest package, which is written in C++.)

The tutorial notebook runs through the steps to user install the bagpipes package and build its dependencies on the RSP so that it can be used both from the python command line shell and from inside a notebook.

The basic steps are:

Open a terminal in the Notebook aspect of the RSP.

Install the bagpipes package with pip:

pip install --user bagpipes

(The

--userflag is necessary because you don’t have root access.)Among other packages, the above command installs

PyMultiNest, a python interface for MultiNest. TheMultiNestpackage itself is not included. Before we can use thebagpipespackage, we must install MultiNest and update theLD_LIBRARYenvironment variable.Install and build the dependencies – in this case, the

MultiNestpackage – in your~/localdirecotry. In a terminal, execute:cd ~/local git clone https://github.com/JohannesBuchner/MultiNest cd MultiNest/build cmake .. make

Update the

LD_LIBRARY_PATH` in your ``~/.bashrcfile (for terminal-based access):export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=${LD_LIBRARY_PATH}:${HOME}/local/MultiNest/lib

Update the

LD_LIBRARY_PATH` in your ``~/notebooks/.user_setupsfile (for notebook access):export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=${LD_LIBRARY_PATH}:${HOME}/local/MultiNest/lib

The first time you perfom Steps 4 and/or 5, log out and log back into the RSP.

For more information, please consult tutorial notebook for working with user packages.

Do I need to know Git?¶

Although use of Git and GitHub are not necessary for DP0 participation, most Rubin Observatory staff and LSST Science Collaborations use Git and GitHub, and it is highly recommended for all RSP users. Git is free open-sourced software for change-tracking and version control of any set of files that are edited by one or more contributors. GitHub is a web-based provider for Git functionality, plus it offers a few of its own features. In this Community Forum thread, everyone can find and share resources for learning about Git and GitHub. A few of the Troubleshooting tips below involve the use of Git.

What is the Butler?¶

The Butler is a middleware component of the Data Management System (DMS) for persisting and retrieving datasets. The third generation “Gen3” Butler is the version being used for DP0.2. Full Butler documentation is available, and several of the Notebook tutorials demonstrate Butler use as well.

How do I ask questions about Notebooks?¶

Keep in mind that if you are not experienced at accessing data via Jupyter notebooks, or using a Science Platform more generally, you are not alone! Most of the DP0 delegates are new to this environment, and all of your questions and feedback will help us improve both the documentation and the tools.

The DP0 Delegate Homepage provides information about Getting support at any time via the Rubin Observatory Community Forum or via GitHub Issues. Another option is to attend the biweekly DP0 Delegate Assemblies which will feature live tutorials and question-and-answer time with Rubin Observatory staff.

Beginner-level questions are very welcome, both in the Community Forum and during the Delegate Assemblies. To encourage questions in the Forum, a couple of beginner-level topics have been started to share resources for learning python and SQL. People new to the Rubin Community Forum might appreciate this video demonstrating how to navigate and post topics to the forum.

Can you install the lsst.rsp module outside the RSP?¶

Yes, you can indeed install lsst.rsp on your own computer and run it locally. It is a standard PyPi package and can be installed by using pip install lsst-rsp.

Note that if you want to use it to access data that is hosted at the IDF, you will also need a security token. See this documentation here: https://nb.lsst.io/environment/tokens.html for how to get a security token.

As an example, we will walk through how you can access the Rubin LSST TAP service locally.

After getting an access token, set the value of the environment variable ACCESS_TOKEN to the path to your token.

Then set the TAP URL endpoint EXTERNAL_TAP_URL to "https://data.lsst.cloud/api/tap" (e.g. for macOS, execute the following)

export EXTERNAL_TAP_URL="https://data.lsst.cloud/api/tap"

In a python shell or notebook environment, you should then be able to execute the following:

from lsst.rsp import get_tap_service, retrieve_query

service = get_tap_service()

query = "SELECT * FROM tap_schema.schemas"

results = service.search(query).to_table()

print(results)

Although the LSST environment can be run locally, we strongly recommend to use it in the RSP environment.

Troubleshooting tips¶

How to recover from package import errors (ImportError)¶

The Problem: In this case the problem manifests when a package cannot be properly imported. This leads to an ImportError for which the last line of the traceback actually points to the file it is trying to import from, and it is in the user’s “.local” directory.

If a user sees a mention of “.local” anywhere in the exception, there is a chance they have installed packages that are polluting stack environments, and this is a big red flag that following the solution below will be necessary.

However, this is not the only way this problem can manifest, as issues with user-installed packages can be hard to track down. E.g., it might import fine, but then not be able to find an attribute or method on a particular object.

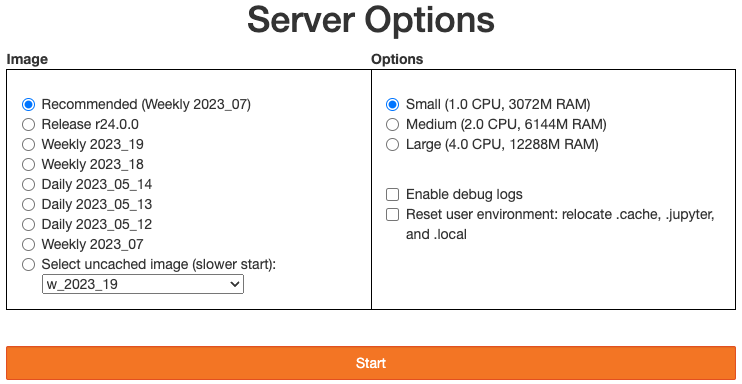

The Solution: Users should exit the RSP and then clear their “.local” file when they log back in to the Notebook Aspect by checking the box “Clear .local directory (caution!)” on the Hub spawner page (see the “Server Options” image at the top of this page). This option is simple and effective, and also helps in cases where the user-installed packages are keeping JupyterLab from starting.

An Alternative Solution: The user should first close and shutdown the notebook (or, e.g., ipython session) which is experiencing the error, and then launch a terminal in the Notebook Aspect and move their “.local” file out of the way by renaming it as something else, such as:

mv ~/.local ~/.local_[YYYY][MM][DD]

There will be no need to recreate the “.local” directory after this. The user should then restart the notebook (or, e.g., ipython session) and try to import the packages.

How to make Git stop asking for my password¶

It is recommended that all Git users working in the RSP configure Git and set up an SSH key. First, using a terminal in the Notebook aspect, set the global Git configurations.

git config --global user.email yourEmail@yourdomain

git config --global user.name GitUsername

Then, using a terminal in the Notebook aspect, follow these instructions for generating a new SSH key and adding it to the ssh-agent. Be sure to follow the instructions for the Linux environment (i.e., the RSP environment), regardless of your personal computer’s environment, because you are generating an SSH key for your account in the RSP.

When you git clone new repositories, use the SSH key.

If successful, you will be able to git fetch and git push without entering your Git password.